Century Songs is a deep dive into the songs that have meant the most to me in the 21st Century so far, 2000-present. The songs are not ranked, and I’ll be writing about whichever ones seem right that week. For an overview of the project, click here.

On December 6, 1991 in Austin, TX, four teenage girls were brutally murdered in a frozen yogurt shop. It’s a horrific crime, and the details can be found in this Wikipedia article if you are curious, along with information on the arrests, convictions, and subsequent overturning of those convictions and release of various suspects over the years, including several teenage boys, based on false confessions, tainted evidence, and egregious errors by the investigators. To date, the murders remain unsolved.

In much the same way that morbid stories of real murders have inspired tens of thousands of hours of true crime podcasts, songwriters have used such grim historical reference points for centuries, particularly in traditional American folk music. While the definitions and context can be a little fuzzy, these “murder ballads” tend to be based on real crimes, typically perpetrated by men against women (although more on that later), and often play as cautionary or morality tales — although to be honest it usually just seems more like audio voyeurism instead.

Where it can get a bit murky is when a murder ballad is wholly fictionalized (think The Chicks’ “Goodbye Earl,” which is neither about a real murder nor a ballad, but the video does feature Jane Krakowski so it gets a nod here) or, in the case of Okkervil River’s “Westfall,” the story is about a completely fictionalized murder based on real events. Personally, I think “Westfall” counts because it doesn’t just recount a terrible act, it considers the very nature of evil and what we might learn from it, before ultimately concluding there may be nothing whatsoever to learn.

Okkervil River formed in Austin by singer/songwriter Will Sheff in 1999, relocating there from New Hampshire and playing a sort of hyper-literary rootsy Americana that wouldn’t sound out of place on most indie movie soundtracks of the era. They run in the same circles as another thoughtful indie band primarily led by one man, Shearwater’s Jonathan Meiburg, and found a home on Bloomington, IN label Jagjaguwar, with whom they would work for the next decade.

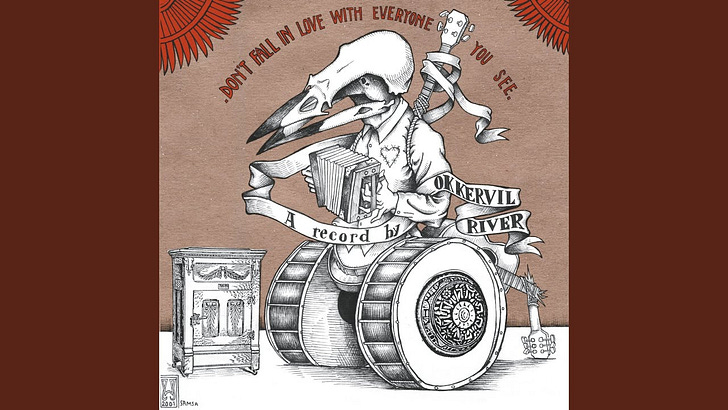

Although they self-released an EP and an album before it, their proper debut is arguably 2002’s Don’t Fall in Love with Everyone You Meet, which is both a good album and even better advice. The album is warm and earthy, with a rustic, homemade sound and lyrics that invoke specific places and even more specific feelings, especially in song titles like “Dead Dog Song” and “Listening to Otis Redding at Home During Christmas.” And then, of course, “Westfall.”

Whether or not “Westfall” officially counts as a murder ballad is dependent on the strictness of your definition. It’s true that the details of the story in the song are completely different from the 1991 events in Austin, with Sheff changing the circumstances so that he would feel comfortable telling the story from a first-person perspective, which is generally more traditional. Take, for example, “The Knoxville Girl,” an Appalachian murder ballad itself derived from 19th Century Ireland with an English variation going back even further. It’s a brutally blunt story of the murder of Anne Nichols by a local man named Francis Cooper, and while the lyrics are matter-of-fact and unapologetic in their description of the act, at least the song ends with the narrator rotting in prison, whatever good that does poor Anne (who doesn’t even get named in the song).

And while it’s true that a majority of murder ballads are stories of men committing crimes against women, there have been several instances of women flipping the script, whether they are writing as victims or killers themselves — sometimes both. One particularly twisty example is “The Night the Lights Went Out in Georgia,” first recorded by Vicki “Mama’s Family” Lawrence in 1972, later covered by the likes of Tanya Tucker and Reba McEntire. In the song, which as far as I can tell is entirely fictional, the unnamed female singer’s brother discovers his wife has been unfaithful, hearing it from a man named Andy, who tells him, “To tell you the truth, I’ve been with her myself.”

Naturally, her brother “sees red” and goes home to get his gun and prepares to kill his wife and Andy. Only when he gets there, he finds tracks in the snow, Andy already dead, and his wife “musta left town.” The trial is quick, the brother is hanged, and our sweet-voiced narrator delivers the punchline:

“Well, they hung my brother before I could say

The tracks he saw while on his way

To Andy’s house and back that night were mine

And his cheatin’ wife had never left town

And that’s one body that’ll never be found

See, little sister don’t miss when she aims her gun”

Other murder ballads by women are more direct, more visceral. Take Gillian Welch’s 1998 song “Caleb Meyer,” written by Welch and frequent collaborator David Rawlings, and tells the story of a woman named Nellie Kane who kills her would-be rapist in self-defense — specifically she slashes his neck with a broken whisky bottle that Caleb had brought with him. There is nothing titillating or romantic in “Caleb Meyer,” and no easy answers are given, but there is also no regret.

“Caleb Meyer your ghost is gonna

Wear them rattling chains

But when I go to sleep at night

Don’t you call my name”

Both Lawrence’s and Welch’s songs are, or at least appear to be, entirely fictional, even if their events are rooted in very realistic and dramatic scenarios. For “Westfall,” what drew Will Sheff to the 1991 murders wasn’t the macabre details of the crimes themselves, but rather for the aftermath and the trial of one of the eventual accused. (To be clear, the conviction was overturned in 2006 because it was believed the defendant had not received a fair trial.) But before we get to the core of the song, we have to set the stage for “Westfall.”

The song opens up with the narrator in his home completely surrounded by police. “They’re gonna take me, throw me in prison, I ain’t comin’ back again.” We don’t yet know what he has done, or why he’s in this situation. It’s a fantastic opening, and you can’t help but keep listening to the story.

When I was younger, handsomer and stronger

I felt like I could do anything

But all of these people making all these faces

Didn’t seem like my kith and kin

A young man, full of confidence, good-looking and probably easily able to relate to people, especially girls. But something is perhaps amiss. A sociopath, maybe, who looks at people not as equals but as something foreign, something unalive, easily manipulated, perhaps.

Our narrator does have one friend, though: Colin Kincaid, a 12th grader, who lives in a “big tall house out on Westfall / where we would hide when the rains rolled in.” Remembering that the 1991 murders were at the time suspected to be carried out by teenagers, the darkness already begins to creep in. We may not know anything about the boys’ relationship, but that future police presence is still fresh in our minds.

“We went out one night and took a flashlight

Out with these two girls Colin knew from Kenwood Christian

One was named Laurie, that’s what the story

Said next week in The Guardian”

What I love about this verse is the details that say so much about our narrator. The two boys go out at night with two girls that one of them apparently knew from school. One of them was named Laurie, and our narrator only knows this because he read it in the newspaper the following week. If he knew it then, he didn’t even bother to remember it — which is made all the harrowing by the next verse. But why would her name be in the newspaper? What happened that night? Well, it is a murder ballad, after all.

“And when I killed her it was so easy

That I wanted to kill her again

I got down on both of my knees and

She ain’t coming back again”

The first time I heard this song I was floored. The abruptness and coldness of this verse, anchored by driving guitars and mandolin, the full band kicking in for this part. We have no idea why this burst of violence happens, but as we’ve seen, we can’t say it’s wholly unexpected. Sheff also doesn’t revel in the details; in “The Knoxville Girl,” we get several lines detailing the murder itself, from the murder weapon to her final resting place. Even in “Caleb Meyer” the cause of death is clear, detailed. Sheff isn’t interested in this. We don’t even know what happened with Colin and the other girl — although we can guess, considering the inspiration for the song.

Speaking of the inspiration for the song, as I said it wasn’t the murder itself that so motivated Sheff. In an interview with the Comes with a Smile zine, he said this of the song:

“The authorities caught one of the guys who did it recently and before long the local news networks started airing courtroom footage of him, the secret reason - to my mind - being so that the folks at home could scan his televised face for the evil hiding behind it. I recall thinking that evil isn’t as easy to detect as that.”

The memory of staring at the television screen, into the possible face of evil, scrutinizing it for any sign of something being off: that’s the crux of the song and the entire motivation for writing it. For Sheff, evil turns out to look like… nothing of note.

“Now, with all these cameras focused on my face

You would think they could see it through my skin

Looking for evil, thinking they can trace it, but

Evil don’t look like anything”

The line “evil don’t look like anything” is the money line, and Sheff knows this because it gets repeated numerous times in the song’s outro. How many times have you looked at the face of a killer, either on television or in photographs, and wondered about the mind behind the eyes, the face, the smile? Shouldn’t someone have been able to see something sooner? Not necessarily. Evil isn’t obvious, it doesn’t announce itself, and it most certainly doesn’t look like anything.

Whether or not “Westfall” is officially a “murder ballad,” it’s a harrowing listen and a compelling story with a very real, very monstrous event at its core. Even if the names and the details have been changed, Sheff makes his point known and delivers what I think is one of the most fascinating songs of the century so far, and one that’s worthy of any true crime podcast.

Next week: Go back to a simpler time, when the village had all we need and stonecutters made things from stones